Written by Sarah MacPherson

Lead Teacher Sacramento Teaching Preschool

Parkrose School District/ Preschool For All

In September 2022 I returned to preschool after teaching in elementary classrooms for nearly eight years. This was an exciting time of growth and change for early childhood education in Multnomah County, Oregon because the Preschool for All initiative had recently passed. PFA’s mission is to provide free culturally responsive and inclusive preschool for children ages 3-4. As a longtime believer in universal preschool and someone who voted for PFA, I was excited to be a new teacher in the pilot year of this program at Sacramento Elementary in the Parkrose School District. Sacramento is situated in urban Northeast Portland in a residential neighborhood sandwiched between busy interstates and the airport. The children registering for preschool live inside district boundaries, many within walking distance of the school. The community is rich in a diversity of home languages ranging from Tigrinya, Vietnamese, Arabic, Spanish and English. Children came from a wide range of economic diversity, family structures, and religious beliefs as well.

The adults supporting the preschool classroom represent a variety of cultural backgrounds from Eritrea, Myanmar and white American. As a white teacher who grew up with numerous privileges, I have a responsibility to constantly examine my own beliefs, seek feed back, and question the roots of the choices I am making as a teacher. Left unexamined, I know that my own implicit biases will inhibit children from engaging, connecting with each other, and finding belonging in their classroom community. This knowledge coupled with the newness of preschool left me in a lot of uncertainty! Past experiences have shown me that when I am in disequilibrium the best gift I can give to myself and the children is to slow down, ask questions, observe, and listen. Doing so creates space for the children to discover and reveal who they are and what they need so I can meet them there.

back, and question the roots of the choices I am making as a teacher. Left unexamined, I know that my own implicit biases will inhibit children from engaging, connecting with each other, and finding belonging in their classroom community. This knowledge coupled with the newness of preschool left me in a lot of uncertainty! Past experiences have shown me that when I am in disequilibrium the best gift I can give to myself and the children is to slow down, ask questions, observe, and listen. Doing so creates space for the children to discover and reveal who they are and what they need so I can meet them there.

In those first few weeks together we all encountered so much newness. Over and over again in numerous ways I observed children asking, “Do you see me? Do you hear me? Do I matter? Do I belong here?” This looked like Mateo’s shoe coming untied and suddenly finding him crouched down at my feet silently staring at his laces, it looked like Sofia saying, “teacher” and when I replied “what?” she had nothing more to say, it looked like Levi standing on the periphery to narrate what he saw other children doing, and it looked like Remi tapping me on the arm in moments when he appeared fully engaged and joyful to remind me, “I still miss my mom.” Children ask, “do you see me?” in a million different ways everyday and when adults and peers reflect back “I see you” we set the foundation for belonging. This became the lens through which I viewed everything we did together.

Every morning we began the day outside eating breakfast and playing. On one corner of our playground there is a small circle of Douglas Fir trees. This space called to all of us and it was there that the children started to build a deeper connection with one another. Although exploring the natural world wasn’t the main intention of my work this year, I have found that being in relationship with living creatures and plants while in community with others is foundational to a sense of belonging. We began a morning ritual of walking amongst these trees.

As we explored this new outdoor space I paid close attention to the many ways children were asking for “Do you see me? Hear me? Do I belong?” I knew this would give me a deeper lens into who they  are and what they cared about. I heard them begin referring to themselves as “explorers” saying, “let’s go on an adventure!” These became some of our first shared expressions. Each morning they would run to the trees, look them up and down, and exclaim “Look! I found honey!” They dove in with all their senses; touched it, looked closely with magnifying glasses, traced the goopy trails of sap, smelled it, and wondered why some trees had so much and others had very little. Their attention was showing me what they cared about. I saw an opportunity to reflect back, “I see you” and “your ideas matter.” I snapped photos every morning and projected them on our big screen during morning meetings to invite community dialogue. I heard new theories and asked follow up questions:

are and what they cared about. I heard them begin referring to themselves as “explorers” saying, “let’s go on an adventure!” These became some of our first shared expressions. Each morning they would run to the trees, look them up and down, and exclaim “Look! I found honey!” They dove in with all their senses; touched it, looked closely with magnifying glasses, traced the goopy trails of sap, smelled it, and wondered why some trees had so much and others had very little. Their attention was showing me what they cared about. I saw an opportunity to reflect back, “I see you” and “your ideas matter.” I snapped photos every morning and projected them on our big screen during morning meetings to invite community dialogue. I heard new theories and asked follow up questions:

Mia: Honey is inside all of the trees.

Mia: Honey is inside all of the trees.

Teacher: How could honey have gotten inside?

Stella: I think it’s from the bees!

Eden: The QUEEN BEE! I saw a door on the tree once. That’s where the queen lives.

Arlo: Bees make the honey and they live inside of the trees so that’s why the honey is in the tree.

Stella’s idea of living bees in our special place presented new possibilities and inspired big shifts in the children’s play. At the easels, in small world, in dramatic play, and in their stories the bees became central characters. They had wants, needs, loved ones, worries, and comforts. There was magic and joy in the imaginary world where the bees lived and, at the same time, the bees’ likes and dislikes were grounded in what the children themselves liked and didn’t like. The pretend play about the bees embodied pieces of the children’s own identities and became vehicles through which children were sharing pieces of themselves and encountering one another.

comforts. There was magic and joy in the imaginary world where the bees lived and, at the same time, the bees’ likes and dislikes were grounded in what the children themselves liked and didn’t like. The pretend play about the bees embodied pieces of the children’s own identities and became vehicles through which children were sharing pieces of themselves and encountering one another.

Had I not been clear on my own intentions as a teacher, it may have seemed logical to disrupt the imaginary theories about the bees to present the children with scientific facts. Obviously I knew the sap was not honey. I could have worried that children lacked a scientific understanding of trees. I could have brought them books and research to prove what sap was. They probably would have listened and even been interested for a time. But, what would have been lost if I’d done this? Would children trust that school is a place where their ideas matter if my response to them was to bring in adult research with the intention to be “correct?” It was more important to me that they realized that their ideas and understandings of the world both impact and are impacted by their community. Each individual needs their community to grow ideas and the community needs them. This is what belonging began to look like with these children.

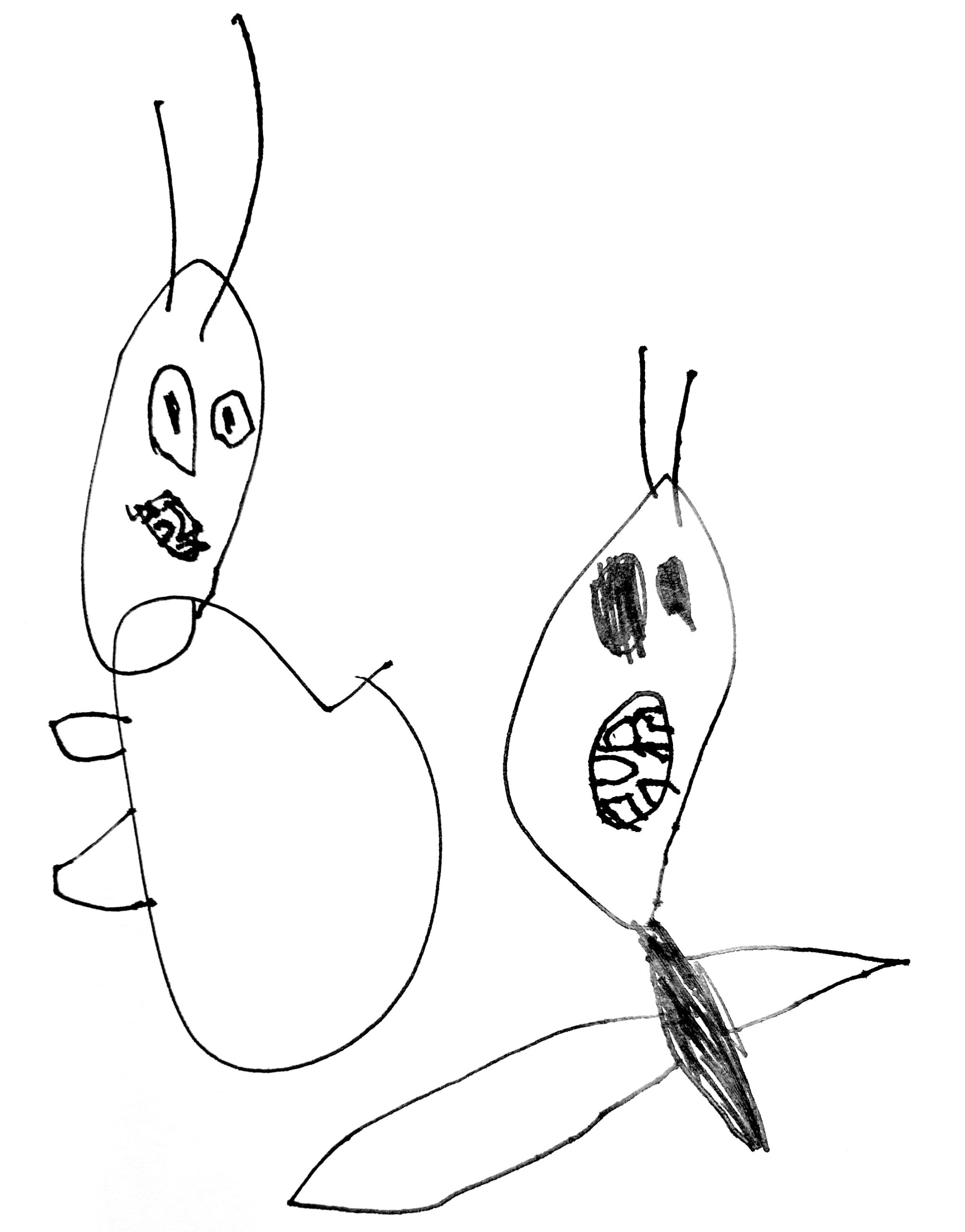

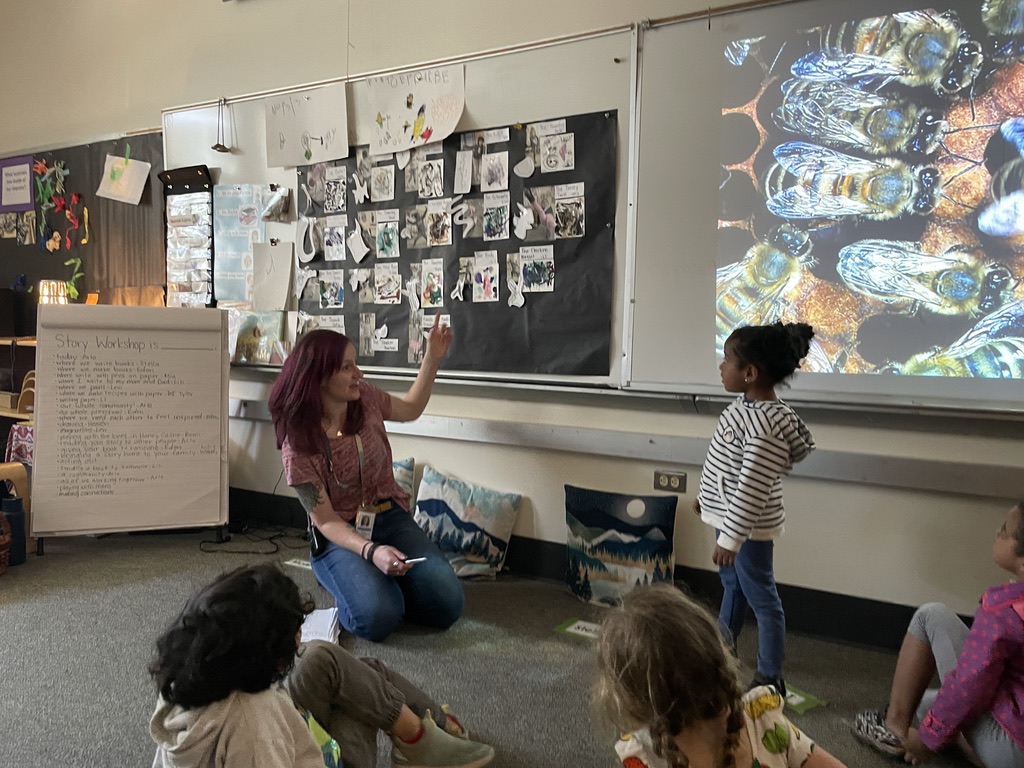

In responding to their curiosities about the bees, I intentionally crafted new playful research opportunities. I added small bee characters to loose parts and invited children to construct what they thought was inside the honey trees. We used clay to mimic the texture of honeycomb. We wrote stories about the bees during Story Workshop, we examined honey comb on the light table, and we captured noticings and wonderings in many ways.

In responding to their curiosities about the bees, I intentionally crafted new playful research opportunities. I added small bee characters to loose parts and invited children to construct what they thought was inside the honey trees. We used clay to mimic the texture of honeycomb. We wrote stories about the bees during Story Workshop, we examined honey comb on the light table, and we captured noticings and wonderings in many ways.

As children researched I heard them continue revealing what mattered to them and how they were exploring who they were in relationship to the world:

Wendy: The bees have mom’s houses too. Their mom’s house is inside the tree.

Elisamadai: Sometimes they miss their moms.

Elsie: They want to know how to skip in their big boots!

Tyler: Do you feel sad sometimes, bees?

Mia: The bees love basghetti restaurants.

Arlo: Bees have spinny toys. They need to play too!

Mia: Bees need all their bee friends.

One wintery Monday morning after a heavy weekend windstorm, we set out to one of our favorite Honey trees. As we approached I saw something large sitting in the grass. Arlo did as well and called out,  “Look! There’s a soccer ball under the honey trees!” As we got closer it became clear to me that what we spotted in the grass wasn’t a soccer ball at all…it was a large paper wasp nest!

“Look! There’s a soccer ball under the honey trees!” As we got closer it became clear to me that what we spotted in the grass wasn’t a soccer ball at all…it was a large paper wasp nest!

I quickly went ahead to ensure safety before the children got close. Although we could see larvae inside the comb, there weren’t any active bees. We made some safety agreements and the children circled around the hive. We were in awe of how beautiful it was and also the connectedness to our work! I asked, “What could have happened here?”

Wendy: It just fell from the clouds or something!

Levi: The bees lost their home.

Eden: From the tree! It fell from the tree!

Mateo: I agree with Eden. I think it was up in the honey tree!

Stella: But why would it fall out?

Levi: I think the bees have no home now. That’s sad.

Eden: It’s sad because now where do they live?

Heaven: It wasn’t strong enough?

Teacher Sarah: What do you mean, Heaven?

Heaven: It wasn’t strong enough to hold onto the tree.

Wendy: It had to hold on tight but it just couldn’t.

Remi: The bees just lost it!

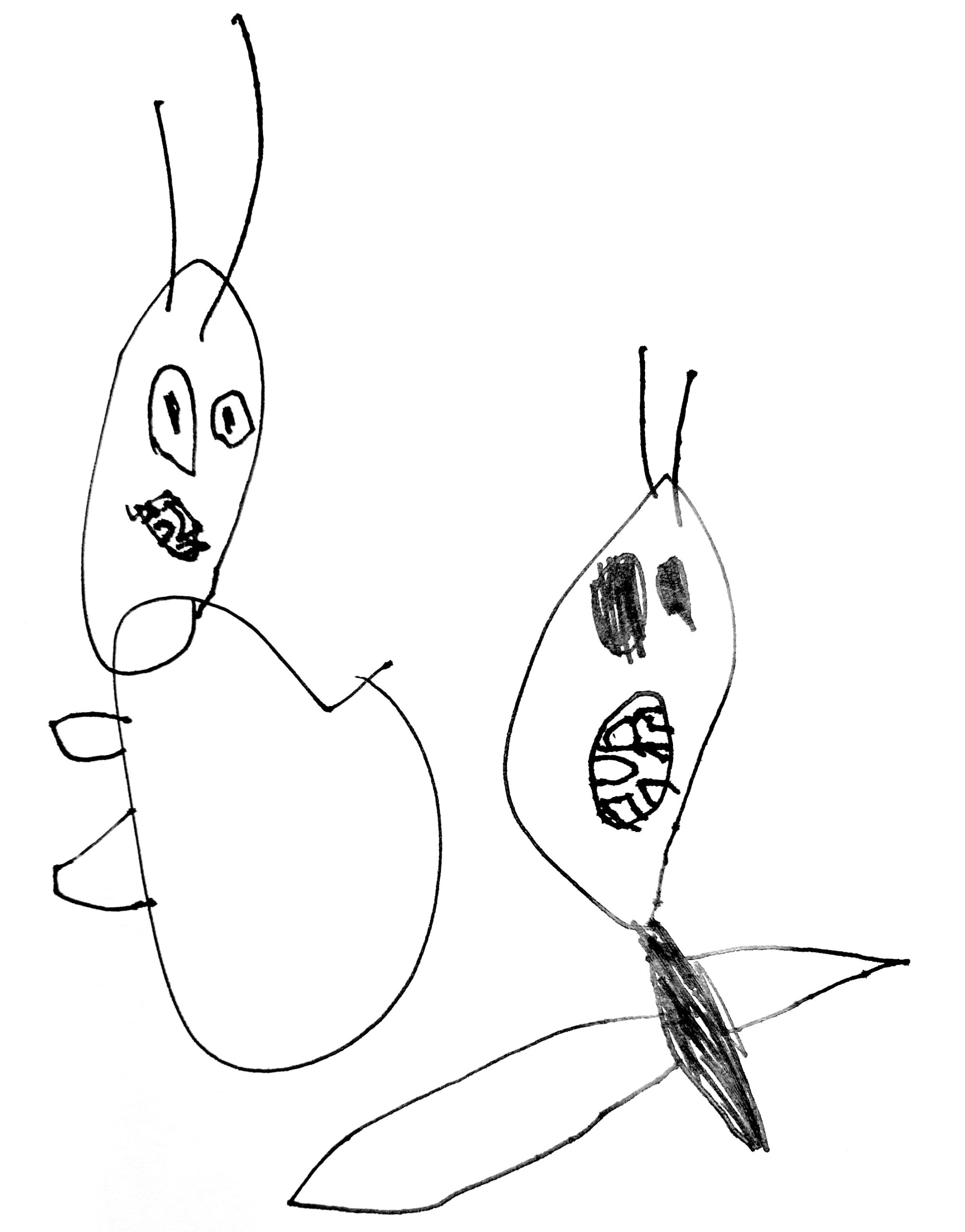

We spent time marveling over this discovery and then I collected the hive in a box, contacted a beekeeper to ensure it was safe to bring inside, and upon receiving assurance put it in a display case for us to examine more closely.

As we observed, similar themes continued to emerge. The children’s concern that the bees had lost their home was very personal for these specific children. Housing insecurity is something I knew some families had experienced and all of these children live in a neighborhood where a trip to the grocery store a few blocks away reveals the injustices houseless people are facing in our community on a daily basis. Loss of home was a very real and deeply rooted concern for these children. It was also a profound opportunity for me to reflect back, “I see you, I hear you, your concerns matter.”

As we went for adventures the next few mornings I noticed children looking for clues in the area where we’d found the hive. This was a truly authentic opportunity for me to live in inquiry with the children; I didn’t know where the bees who had occupied the hive were, exactly where the hive had come from, or for certain that the bees were okay. I listened to their questions, experienced empathy with them, and wondered myself.

One morning, as children were choosing where they wanted to play, Eden raised her hand and announced, “I’m going  to big blocks! I’m going to build a castle for the bees. I need four friends to come help me!” Immediately hands went up hoping to be one of Eden’s collaborators. I was so curious what had inspired Eden so I asked her and she said, “I want the bees to come visit us in preschool! Honey Castle is a gift for the bees!” The children went to big blocks and began what became a week’s long construction project. In reflection, I now recognize the significance of Eden’s invitation. Eden’s desire to build a castle for the bees might be interpreted as an attempt to help. She was in community with others who saw the loss of a home as a significant problem too. She felt connected to her community and she knew that they cared about the bees and in turn her idea. By this point in the year we had created a community in which the children trusted each other to care for their ideas so collaboration was the natural path forward. Mutual care for the bees and for one another!

to big blocks! I’m going to build a castle for the bees. I need four friends to come help me!” Immediately hands went up hoping to be one of Eden’s collaborators. I was so curious what had inspired Eden so I asked her and she said, “I want the bees to come visit us in preschool! Honey Castle is a gift for the bees!” The children went to big blocks and began what became a week’s long construction project. In reflection, I now recognize the significance of Eden’s invitation. Eden’s desire to build a castle for the bees might be interpreted as an attempt to help. She was in community with others who saw the loss of a home as a significant problem too. She felt connected to her community and she knew that they cared about the bees and in turn her idea. By this point in the year we had created a community in which the children trusted each other to care for their ideas so collaboration was the natural path forward. Mutual care for the bees and for one another!

Honey Castle grew daily and soon we entered into a design process that would transfer it from a delicate block structure to sturdy cardboard. Curiosity about the hive also continued to appear in their play as they built the castle. One idea that kept appearing in their play was that bees sting. After finding the hive Stella suggested that maybe some “mean bees” knocked it down and then Mateo replied with, “They should sting the mean bees! Protect their hive!” Further, as children were building Honey Castle, I often heard them say that if another creature tried to harm the castle the bees were prepared to sting. Sometimes the sting even came across as a scary attack by the bees!

Honey Castle grew daily and soon we entered into a design process that would transfer it from a delicate block structure to sturdy cardboard. Curiosity about the hive also continued to appear in their play as they built the castle. One idea that kept appearing in their play was that bees sting. After finding the hive Stella suggested that maybe some “mean bees” knocked it down and then Mateo replied with, “They should sting the mean bees! Protect their hive!” Further, as children were building Honey Castle, I often heard them say that if another creature tried to harm the castle the bees were prepared to sting. Sometimes the sting even came across as a scary attack by the bees!

This brought about a tension that I saw as an opportunity; the children loved the bees so deeply yet they also knew the bees could potentially hurt them. Within this dynamic there was a metaphor about relationships, something most of these children were navigating with peers for the very first time. When presented with complex questions like this, I don’t believe it’s my job to offer the children certainty. Doing so often harmfully glazes over the many layers and perspectives that the question holds. Learning doesn’t happen in the certainty; learning happens when we explore the uncertainty together, navigate the push and pull, take on different perspectives, and settle into complexity without absolutes. I knew the children were capable of this because I saw them navigate this tension with each other everyday! They hugged and hit each other, they shared and also snatched materials away from each other, they said “do you want to play with me?” and also, “no you can’t play.” The children loved each other and they were stinging each other all at the same time! This is the complexity that comes with a sense of belonging within a community.

As had been the pattern so far, exploring stinging through the bees was a vehicle for the children to explore and share pieces of themselves. I asked them, “Why do bees sting?” and listened intently to their ideas about bees. I knew this would reveal some of the reasons why children “sting” each other too:

Teacher Sarah: Why do bees sting?

Elsie: They feel worried. Maybe they will lose their home again?

LT: Someone might kick them or step on them so they sting the person to be safe.

Arlo: Yeah, they’re worried a person will hurt them.

Wendy: They want to be friends.

Eden: They have to protect their honey.

Not surprisingly they articulated dynamics within our community. We all have needs and when we feel worried that somebody else might do something that interferes with us getting our needs met, we react from fear and emotion. Sometimes the reaction hurts another person’s feelings or even their physical body; we sting each other. And then, after the sting, healthy communities take time to reflect and turn back towards each other with curiosity that communicates “I see your pain” and listening that says “I hear you even if I disagree with you” and empathy that shows “you matter here.”

I heard the children saying that stings communicate worry, fear, a desire to feel safe, or to protect. Verbal communication was only one of many, many ways children were going about getting their needs met everyday at school. I wondered if we might have fewer stings if we were more apt to pay attention to all forms of communication. I also recognized that, like many of the children who were encountering unfamiliar forms of communication with each other, we were also not sure how bees communicate. Yet, if we were truly constructing a castle where the bees could feel safe and comfortable, we probably needed to communicate with them to find out what they needed! I wondered how a close examination of the ways bees communicate might support children to attend to the diverse ways they communicate with each other.

The bees don’t speak in the ways that we do…how can we know for sure what they are communicating? Just like us, the bees want to feel seen and heard and to know that they matter. Children went outside everyday as researchers looking for clues on how bees communicate.

The bees don’t speak in the ways that we do…how can we know for sure what they are communicating? Just like us, the bees want to feel seen and heard and to know that they matter. Children went outside everyday as researchers looking for clues on how bees communicate.

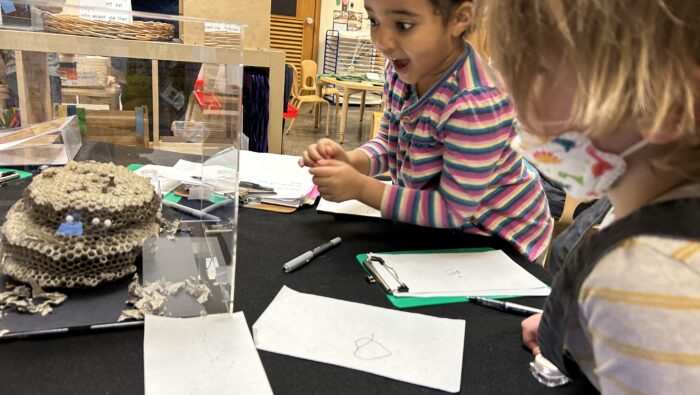

We also read books that offered insight into how hives work together and the different roles bees play in their communities. One book that was central to our work is called Bee Dance by Rick Chrustowski. It outlines the pattern of the waggle dance and explains how bees use it to communicate. Mateo said, “I know what this means! Bees talk by dancing!” and Elsie added, “We need to dance!”

The next morning Waggle Workshop began!

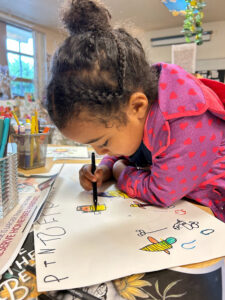

Children joined me on the carpet two at a time to dance to music. It was important that we remained centered on diverse forms of communication so I offered them opportunities to physically move their body and then represent their dance moves in a variety of materials.

They translated their movements in materials like black lined pen on paper, watercolor, and wire sculpture.

Over time, children developed a signature move that they named and taught to the whole community. Then, we began stringing moves together into one dance routine.

At this point it was spring and I began to envision what a culminating experience could look like. I envisioned a performance for parents and hoped the children would have an experience of growing something in community with each other. With this idea in the back of my mind, we continued going for morning adventures…and something surprising began to happen. Over the course of a few weeks we found four dead bees outside.

Naturally, the children were concerned! They had many theories about what might have been happening to the bees. I had been listening for a while considering the right time to bring the children some science around problems bees are facing in the world; this was important to me because I knew that the love the children had developed for the bees was a strong foundation for advocacy. I wanted them to have a shared experience of identifying a problem, caring deeply about something, and acting as empathic citizens to generate change.

Naturally, the children were concerned! They had many theories about what might have been happening to the bees. I had been listening for a while considering the right time to bring the children some science around problems bees are facing in the world; this was important to me because I knew that the love the children had developed for the bees was a strong foundation for advocacy. I wanted them to have a shared experience of identifying a problem, caring deeply about something, and acting as empathic citizens to generate change.

We spent a few weeks studying the dangers of pesticide use and the need for native plant species. I also began a mini genre study with children on signs because I had seen them express interest in signs around our school already and I wanted to offer them a new medium for communicating and sharing their ideas, as well as an authentic opportunity to write and listen for letter sounds. Children accepted the invitation and began making signs during Story Workshop that said, “No Pesticides” and “Plant Native Species.”  Ultimately, children decided that we needed to plant a native species garden for the bees at our school. We spent days studying various native species, voting on which ones we’d like to plant and where, and when we had formulated a solid plan we wrote a letter to Principal LC telling her the species we’d chosen to plant, why the bees need them, and we proposed a garden location. Arlo added, “Maybe if we plant native species outside of school without any pesticides on them the bees will come visit us more?”

Ultimately, children decided that we needed to plant a native species garden for the bees at our school. We spent days studying various native species, voting on which ones we’d like to plant and where, and when we had formulated a solid plan we wrote a letter to Principal LC telling her the species we’d chosen to plant, why the bees need them, and we proposed a garden location. Arlo added, “Maybe if we plant native species outside of school without any pesticides on them the bees will come visit us more?”

Principal LC visited us and asked some great follow up questions and ultimately approved the children’s plan! They were so excited! However, on the morning that we were set to begin gardening, something unexpected happened! As the children were playing on the playground, Principal LC came outside to let me know that facilities had said that in fact we could not begin weeding in that area. It wasn’t safe for the children because over the weekend Parkrose had sprayed pesticides there!

This threw an unexpected, complicated and yet, beautiful wrench into our plans! Right away I began to consider how we would pivot and respond and what authentic possibilities for advocacy work this might present! At Morning Meeting, instead of preparing to go outside in small groups like we’d planned, I delivered the news about the pesticides to the children. They were SO surprised to hear that this problem was happening at our own school!

Elsie: It’s poison!

Stella: The bees will get sick!

Arlo: They want to keep slugs and mice away but it hurts the bees!

Wendy: Oh my gosh!

Elisamadai: The bees get sick and then their moms want to help but they just can’t.

Lili: They just have to stop doing the pesticides!

Eden: They poison the bees…what about the butterflies?

Teacher Sarah: What should we do next?

LT: Let’s hang up our signs!

Sarah: How will that help?

Arlo: The people will read them and then they will know to stop!

Lili: Stop the pesticides!

Teacher Sarah: Who needs to know about this problem?

Mateo: the kids…the teachers…the grown ups!

Stella: Teachers have to know!

Arlo: It’s not just a kid problem!

As the children generated more and more signs, we continued finding dead bees outside and we were puzzled over what to do next with our garden. We rehearsed our waggle dance routine. Parents were set to visit Honey Forest for an end of year performance in just a couple of weeks! I also continued talking with colleagues and researching the impact pesticides have on bees; I wondered if I may find any additional connections that would help the children’s work.

As the children generated more and more signs, we continued finding dead bees outside and we were puzzled over what to do next with our garden. We rehearsed our waggle dance routine. Parents were set to visit Honey Forest for an end of year performance in just a couple of weeks! I also continued talking with colleagues and researching the impact pesticides have on bees; I wondered if I may find any additional connections that would help the children’s work.

Right before our performance, a colleague sent me an article connecting waggle dancing to pesticide use. The science explains that when bees visit flowers where pesticides have been sprayed, the pesticides make them jumble up their waggle dance! The chemicals cause bees to get confused and their dance is no longer accurate, meaning they can’t communicate where the food source is to the rest of the hive.

I shared this research with the children and again we wondered, how can we help? After much brainstorming and researching through play, Lili had a big idea! She pointed at the pictures of our dance moves on the whiteboard and said:

Lili: The bees could come to us if they forgot how to dance. They could come watch us to remember the waggle moves!

Eden: We’ve already been helping! We’ve been dancing in Honey Forest. The bees

have been watching from the trees! They like our waggle dance.

Remi: If they watch us dance then they can remember how to dance.

Stella: Before we dance we have to invite them. We have to say, “bees come out!”

Over the course of the year I had moments of feeling concerned that I wasn’t maintaining a healthy balance for children between being presented with a problem in the world and feeling empowered to fix it. Lili’s idea however offered the possibility that maybe we had already been helping the bees and didn’t even know it! There was a bigger purpose behind our waggle routine…we were doing the important work of helping the bees remember! Their waggle dance was advocacy. And in this advocacy they were proving to themselves, “we all are seen and heard. We belong here. We matter. And how we help matters.”

In the second to last week of school, we danced for families underneath our beloved honey trees. Before each performance the children invited the bees to peek out their doors in the honey trees to watch us. They said, “Bees! We want to help you remember!”

Following our dance performance, the children talked to the bees everyday. During morning adventures we found them on dandelions, in the garden, and in Honey Forest. I heard children asking the bees important questions:

Yousif: Did you like our waggle dance, bees?

Arlo: Bees, did you watch us dance?

Stella: Did we help you remember how to dance, bees?

Heaven: Do you remember now?

Mateo: I hope you can remember!

Wendy: We will show you again if you need more remembering!

We also planted our native species in the school garden. Although we learned that sometimes pesticides are sprayed there too, the children surrounded their planter boxes with signs that read “No Pesticides.”

We also planted our native species in the school garden. Although we learned that sometimes pesticides are sprayed there too, the children surrounded their planter boxes with signs that read “No Pesticides.”

I never could have imagined the work we did together this year and the path that it took. If you would have asked me back in September what we might have studied or paid attention to this year, bees would not have been anywhere on the list. But over the course of this year, the bees captured the attention, awe, and wonder of this group of children. And in doing so, these children found something they cared deeply about in community with each other. This year was ALL about the bees. And also, it wasn’t about the bees at all. What the bees really taught us was about community and belonging. And how we all can help each other belong by communicating “You are seen. You are heard. You matter. You belong here.”